Help:Scanning

Scanning an image or document for Commons can be relatively easy, if you know what you're doing, and, if you have an interest in history, can be an excellent way to share your interest with the world.

Excellent sources of public domain works include:

- Libraries (particularly those of large cities and, even better, Universities, where students and others allowed to use their collections are generally given freer access to the older books than the general public normally is able to get)

- Historical societies

- Used bookstores

- Yard sales and charity shops

General advice[edit]

Check your monitor is adjusted properly, particularly the brightness and contrast settings. Too bright, or too low-contrast and your images will tend to have a grey tinge to them on better-adjusted monitors. You should ideally be able to see three circles on this image, which tests monitor calibration. Commons:Image guidelines#Your Monitor provides more advice.

Unless your scanner is incapable of it, never scan at below 300 dpi[1] The file sizes may be large, but for engravings, paintings, and illustrations of any complexity, this is about the minimal resolution to let it be reproduced to a reasonable quality.

400 dpi is a good general resolution to use, though for engravings and similar works 600 or even 800 dpi is useful, as master engravers (such as William Hogarth and Gustave Doré) often included details smaller than the naked eye can make out. 500 dpi to 800 dpi may also be convenient for images at around the size of a postcard or smaller (about 3" by 4" / 8 cm by 10 cm), as allows for some degree of scaling up above the original size. Likewise, 600 or 800 dpi is a good choice if you're scanning from a rare work – the extra quality will be appreciated, and make sure that 1200 dpi is almost always excessive, unless you're scanning slides or microfilm. If you are, consult your scanner's manual.

Clean your scanner glass off before scanning, particularly if you have pets — hairs, dust, and the like have a tendency to get on the scanner bed.

Use your scanner software's preview option (if it has one) to get the image as straight as possible. Rotation can be done afterwards, but it's often a headache, and if you can get it straight before you scan, you'll have a much easier time of it. Also, every piece of scanner software is different, so learn what functions your scanner software offers [Switch to “Professional” or “Advanced” mode if given the choice], and play around with them until you understand how to use them well.

Make sure the thing being scanned lies flat. If it's just one sheet, place heavy books on it. If you're scanning part of a book, push down firmly on the cover with your hand while it's scanning. Obviously, this does not apply to fragile works.

If it's used at all, autolevels should be used with some caution. Compare the preview with the original (as best you can, given the original is being scanned), and check that the results make sense. If you have any experience with image editing, or think someone interested in image editing might help you later, then turn autolevels off.

If you have a large work that will not fit on a scanner in one piece, don't worry: Graphics labs, such as en:WP:GL/IMPROVE, Commons:Graphics village pump and Commons:Graphic Lab are available, and the people there are usually quite happy to stitch together an image from multiple scans. Tip: It makes things much more easy for them if you use the edge of your scanner's glass to straighten whatever you're scanning against, so that all scans that go into the image are at the same angle. However, if you can't do this, they can usually cope. Also, scan the parts at a fairly large resolution (600–800 dpi is often good): it'll make it easier for the joins between the images to be concealed if it can be scaled down a bit afterwards. Be sure to turn off “autolevels” on your scanner, no matter how good the results of autolevels are normally: two scans done one after another with autolevels off will be a good match in paper tone and colours, and thus much easier to "stitch" together. With it on, you can end up with subtle or even major differences in tone that make the stitching together look a lot worse.

Commons files must be under 100 MB in size. This is almost always ample for both PNGs and JPEGs of up to about 800 dpi resolution at any size that will fit on even the largest scanner. TIFFs can be much larger, but, as explained below, you shouldn't be uploading things in TIFF form anyway.

Reducing bleedthrough[edit]

Already with standard paper thickness, but especially with thinner paper, you can often see the printing from the backside or the next page through the paper. This can be greatly reduced when scanning with a blank paper (or two, if necessary) behind the scanned page. If you have the printing from the backside showing through then you should use black paper for this, if it is only the next page then white is preferable.

You may later want to compensate for the slightly darker white point resulting from black paper behind the page.

If a scan does show shining-through text and you can't rescan as described above, it can sometimes be corrected using image manipulation software. A technique that works quite well for grayscale images is explained at Commons:Pearson Scott Foresman.

Color calibration[edit]

If you want to improve the color accuracy of your scans, manually changing the scan settings can help. For better results, you can buy an IT8 target, which is a sheet of colors that is scanned and then analyzed by software (such as the free LPROF) to create a custom color profile for your scanner.

PNG vs. JPEG[edit]

Please note. The advice below refers to scanned images. If an image has originated from a digital camera, it will usually be in JPEG format. There is no point in changing an image which is already a JPEG to PNG unless you intend to do extensive edits to the image, and want to be able to save your work as you go along (Saving as JPEG repeatedly can greatly increase the amount of JPEG artefacts.) However, such extensive manipulation of digital camera images is only rarely appropriate.

PNG is a lossless method of saving images; GIFs and JPEGs (sometimes called .jpg because of a DOS file name limitation) can add artefacts (ugly errors, pretty much) to your picture. Generally, GIFs are mainly used for animated images, and JPEGs and PNGs are the main choices for still images. As most scanners are not set up to capture moving images, let's concentrate on PNG and JPEG.

PNG is a safe bet in most cases, but if a PNG is very large (more than 12.5 million pixels, or roughly speaking, more than about 4000x3000) Wikimedia software can't show it. A full-colour PNGs can also be quite large in size, though the recent increase in maximum upload size to 100 megabytes helps out a bit here. Programs such as Optipng or PNGcrush can help make your PNG files smaller at no loss of quality. In any case, it's usually best to scan to a lossless format, such as PNG, TIFF, or, if you have to, BMP first. A JPEG has already lost quality, and, with some settings, may have lost a significant amount; switching to PNG will not bring that back. In addition, if you edit a JPEG and save it, particularly if you do this repeatedly, artefacts start to accumulate. By starting with a lossless format, even if you have to go to JPEG in the end due to size issues, you won't lose any more quality than could be avoided.

Best practice: Even if it can't be shown on Wikipedia because of its large size, upload as a PNG as a lossless archival image when possible: You can always upload it as a JPEG as well, and link between them in the "other versions" section of the upload template. This allows any future image manipulation to be done to your lossless PNG, instead of a lossy JPEG.

In better image editing programs, you will get the choice of quality vs. compression for your JPEGs. In general, use the maximum quality 100 - the scale is 1 to 100 with 100 being best quality. In photoshop, which instead uses a 0 to 12 scale, use 12. If the compressed file size exceeds the current limit of 100 megabytes, consider either reducing the quality or, if the material is historically important, requesting assistance at the Commons:Graphic Lab. If the quality is reduced check the image at full resolution before uploading to make sure it still looks okay. This old version of Sadko.jpg, viewed at full resolution, appears to be made up of thousands of little squares, which is one of the things that can happen if the quality is set too low. The current version has twice the file size, but avoids the worst of these problems.

If you have the choice, choose to save PNGs with the "smallest file size" or "highest compression": The PNG compression algorithm is entirely lossless, it just takes a few seconds longer to open or save the more compressed ones - in theory, anyway. In practice, the much smaller filesize makes it so much more efficient that the time spent dealing with the compression doesn't matter.

PNG vs. TIFF[edit]

PNG has much smaller file sizes than most archival TIFF. If you can, scan to PNG, and if you can't — not all scanner software has the option — consider converting to PNG afterwards.

TIFF is offered as a courtesy to any museums or other archives that want to upload their files — as mentioned, not all scanner software can save as PNG, so some archives use TIFF, as something all their scanners can handle. However, TIFF can contain almost any other format — including, in theory, lossy compression algorithms like JPEG! Therefore, if you must use TIFF, ensure you choose a lossless compression, preferably LZW or Zip/Deflate.[2] Baseline TIFF encoders will always produce lossless TIFFs.

Editing your image[edit]

Always upload your original scan, preferably as a PNG or PNG/JPEG pair. This allows people to clearly see what your manipulations were, and allows other editors to fix things if the edits accidentally damage the image.

Common manipulations include:

- Levels adjustment: Adjust colours to better look like the original.

- Cloning out hairs: If you have cats, the chances of at least one cat hair on your scanner is almost 100 %.

- Attempts at restoration: Careful fixing of tears and stains.

These are outside of the scope of this help file. Contact a user experienced in image editing for help with these.

Black and white, grayscale, or colour scanning?[edit]

If your image is in colour, the answer is of course going to be to scan it in colour. For black-and-white images, the decision is a little more complex.

True black and white is usually not a good idea — a grayscale or colour scan tends to look a lot better, showing curves as curves, instead of the jagged edges of a true black-and-white, since it allows anti-aliasing to smooth out pixelisation. However, there's something to be said for both the other choices.

If you're scanning from a reproduction - I was only able to take a photocopy of this newspaper to a scanner - there's little point in keeping the paper texture. This image is scanned in grayscale, with the contrast adjusted upwards in order to provide a smooth, white background, and to get the main parts of the lines pure black. This puts the emphasis squarely on the picture, and, as the lines that make this image up are fairly thick (for an engraving: the smallest are about the width of a line from a ballpoint pen, and are all visible to the naked eye if you look closely), no real loss of detail would come about from such adjustments. This also allows for the image to be printed out without trying to reproduce a paper texture which the paper it's printed on will have anyway.

This is from an original, and is a different type of engraving - a copperplate engraving instead of a woodblock engraving from a newspaper. In this one, some of the lines are so fine that they're hardly visible to the naked eye (at its original size), the ink is slightly tinted from age, and the paper has a nice feel of oldness to it. Some of the detail in the very delicate fine lines might be lost from too much post-processing, and the ink and paper add to the interest of the piece, so this one is best kept in colour. However, it's somewhat harder to print this one

If in doubt, try it both ways, and then decide which one you like best. Note, though, that you can go from colour to greyscale, but not the other way around, so if scanning something quite rare, colour is probably best.

Half-toning[edit]

- Further information: Commons:Cleaning up interference with Fourier analysis

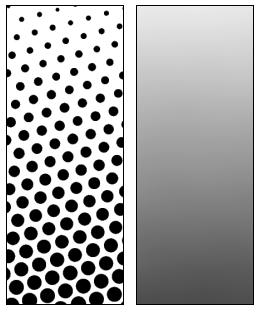

Half-toned images are used in most modern printing. In them, an array of dots is spaced at even intervals, with the size of the dot determining how dark it is. Unfortunately, half-toning can look awful if you zoom in too far and may create disturbing Moiré artifacts. Consider this image:

In the original, this was made by using engraving for the black lines, followed, as I understand it, by either hand-tinting or several additional plates for each colour. However, this version was clearly scanned from a modern book, and at full-view, all the dots that went into the half-toning are visible.

If possible, try to go to the original sources. This, of course, isn't always possible, so if your work is half-toned, but is still under a free licence, please do scan it for commons! At least if scanning resolution was high enough, most half-toning can be fixed with a little manipulation afterwards, and, even if the image ends up, by necessity, at a lowish resolution, it's still showing things that would otherwise be unavailable to Wikipedia projects.

“Remove moiré”, or “descreen” functions of scanner software make a start towards fixing half-toning. But usually the results are not on par with some of the available descreening software. Those functions may be more destructive to the image and may also prevent better descreening software from removing the remaining half-toning artifacts afterwards.

A half-toned image cannot have more detail than the spacing of the dots that make it up, so if your work is half-toned, it's best to manipulate it in a photo editing program afterwards. For that you want to use an oversampled scan (resolution higher than needed to reproduce the smallest details of the actual image). You may want to use a resolution that makes it possible to distinguish the individual printing dots.

Merging dots with Gaussian blur is straight-forward to do and utilizes functions available in most photo-editing software, though it wastes more detail than necessary. Since you have to actually merge the printing dots half-way into each other until the raster fully disappears you end up with only up to half of the original resolution.

For removing dot patterns in the frequency domain you need specialised software, but you can retain nearly all the detail of the full original resolution this way.

Software is available from Cornell University and Picture elements to automatically fix black and white halftone images, if scanned at 600 dpi.

Note: The techniques used for halftoning have changed over time. An early half-toned image (c. 1890-1920) is probably not going to work out with these methods.

Merging dots with Gaussian blur[edit]

Note: This can work out very well in some cases, if done carefully and if you need no more than half of the original resolution. However, it's impossible to reverse, so please upload an unblurred copy as well. Also, note that this should not be done to lithographs or other such images.

Up: Halftone picture.

Middle: Same picture after applying a Gaussian blur filter with σ = 2.

Below: Dot patterns removed in the frequency domain.

(results seen better at full size)

First (maybe after carefully fixing the white-balance) use the Gaussian blur filter with a radius just big enough to make the dot raster disappear. Now you may want to maximise the contrast and maybe do another tonal correction and other stuff. Then you can scale down the image by factor of the blur radius. Because there are no smaller details left this won't hurt much. You may want to use a resampling technique that retains more sharpness instead of having to sharpen afterwards.

In pure black-and-white half-toned images, however, you may be able to get away with just blurring it a bit, then using the sharpen tool and upping the contrast. You should probably downscale it a bit afterwards, but this can salvage a black and white half-toned image to good effect with practice.

Removing dot patterns in the frequency domain[edit]

You need the FFT Fourier plugin (non-Wayback Machine link here) for GIMP and, on top, you may want the descreen script. The descreen script automates the whole process and makes sure you don't miss anything but the built-in despeckling step may be hard to disable and is pretty destructive. (I had to hack the script, unticking the “despeckle” box didn't disable it.) Also, Also, sometimes it bites too hard and introduces echoes around edges. See here for a step-by-step guide on how to manually perform the steps from the descreen script.

This works incredibly well if the patterns to remove really are coherent throughout the whole of the image. If there are (small) areas where the patterns are absent, then the pattern that is removed from the other parts shows up here instead. In this case you may want to load the previous image as a layer underneath the descreened one and merge the undistorted areas in from there, e.g. add an alpha channel to the upper layer and use the eraser tool to make the lower layer show through.

Similarly, if the scanning resolution is so high as to make the printing dots completely separated from each other, then the pattern removal may work less. You may have to try feeding several resolutions of the image into the frequency transform. Initially scanning the image in even higher resolution may yet prove helpful to reduce noise.

Afterwards you may want to decrease resolution to get closer to the original resolution. Finding the right factor of how much to decrease the resolution may be a bit tricky (compared to above blur technique). You may want to try what the minimal blur radius that completely removes the pattern from the original scan as described above under "Merging dots with Gaussian blur" or use the measuring tool to find out the pixel distance between two adjacent printing dots. Now reduce by at maximum half of that factor. (Bitmap graphics need two times the amount of pixels per dimension than the maximum frequency [number of details] to reproduce because of the sampling theorem.) Before resampling you may want to apply other filters like a median filter (“despeckle” in GIMP) to some parts of your image.

[edit]

Engravings are, perhaps, the easiest type of art to work with, and, if you have access to a good library, 19th century illustrated newspapers were common, often had very good quality engravings, used quite a lot of them, and are often fairly-well preserved.

There are two main types of engraving:

The first is to make it out of individual lines, as in this (originally approximately 2" / 5 cm tall) small engraving of Charles Dickens from the Entr'acte, a Victorian theatrical newspaper. This technique is also used for far more complex drawings, for instance:

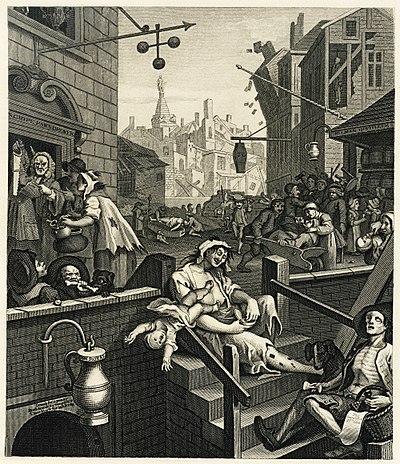

If you look at this image of William Hogarth's Gin Lane at full size, you will see that all the shading, all the detail comes down to fine lines and crosshatching. The fine lines are actually invisible to the naked eye, instead blending into shading.

This is perhaps the most common form of black and white engraving.

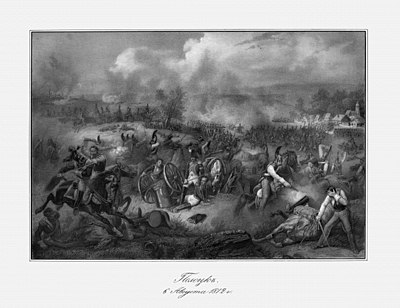

Now consider this engraving:

Technically, this is actually not an engraving, but an etching. An acid-resistant coating was put over the plate, then areas were scratched away to allow acid to get at and texture the plate. The longer the acid is in contact, the rougher the plate's surface gets, and so the more ink it holds. By using several baths, changing what is covered as you go, you can create delicately-shaded works such as this one, with the shading made up of a sea of irregularly-shaped pits. Etching generally cannot get as much detail as an engraving proper, as a certain amount of randomness comes into play from the acid pitting the surface irregularly. An etching is inherently "noisy", with irregular dimpling of black and white, as it's altering how much "noise" there is in any one area that actually makes up the art.

This distinction matters to scanning: In a scan of an engraving proper, every line should be distinct at full resolution, unless the engraving is extremely large, but in an etching, the artist did not physically choose the exact texture that creates the colours or grayscale, so a slightly lower resolution is fine. If you have a choice, somewhere between 300dpi to 800dpi is a good choice, and always go on the higher side for copperplate engravings - the details in a copperplate engraving can literally be microscopic.

A good scan of engraving, etching, or similar should:

- Generally speaking, have a minimum resolution of 300 dpi.

- Show every line that makes it up distinctly, if an engraving. In an etching, it's basically made out of noise/static/irregularly shaped pits, with the location not precisely chosen by the artist. Just scan them at a reasonably high resolution, and make sure all graphical elements are visible.

- If it's a black and white engraving, and you've decided not to show the paper texture, adjust the levels so that the background is smooth, pure white, and the ink (at least where there's plenty of it) is a nice dark black. If you're scanning in colour, still make sure the paper is reasonably light in colour, and black areas do not look washed out, but reasonably black. This will make it look far better when scaled down for viewing on Wikipedia and other projects.

- For colour engravings, see also the advice of the next section.

A note on woodblock engravings[edit]

Woodblock engravings, particularly from Victorian periodicals, often contain fine white lines that show the divisions between the woodblocks that were glued together to make the full image. (Example Image:Design for an Aesthetic theatrical poster.png is fairly cleanly divided into four smaller rectangles.) There are multiple views on whether it is best to edit the image to remove them or to keep them in for authenticity. Graphics labs, such as en:WP:GL/IMPROVE, Commons:Graphics village pump and Commons:Graphic Lab are probably the most useful places to go for restoration work; describing how to do extensive restoration work yourself is probably out of the scope of this tutorial.

Paintings, full-colour illustrations, and similar works[edit]

The methods for scanning full-colour illustrations, paintings (however, see below in this case), and similar are not greatly different from engravings, but it's best to adjust the colours afterwards to make it look as much like the original as possible.

- Scan at a minimum of 300dpi.

- Using a graphics editing program, adjust the levels, brightness and contrast, and so on, until the colours are as similar to those in the actual picture as possible. Keep a copy of the untweaked scan, and compare it with the final version to make sure you haven't accidentally messed something up. Also, this was said in the general advice section already, but make sure your monitor is appropriately calibrated, as described in Commons:Image guidelines#Your Monitor - otherwise, what looks realistic to you and what looks realistic to everyone else will be different.

A warning about paintings: For paintings done on a canvas (e.g. most oil paintings, acrylics, and so on, in most cases, it's not going to be possible to get the original to a scanner, and, if the painting is old, it might damage it even if you could get it to one. If, however, it is possible, and damage is unlikely—e.g. a painting you've just made yourself, hence in good condition, note the texture of it. A little texture is fine, but if some parts stick out much more than a couple millimetres from the surface, you're probably best photographing it.

In many cases, though, you'll be scanning a painting from a modern reproduction. This can lead to mixed results. In lower-quality reproductions, you'll be dealing with half-toning, as described in the earlier section on it. Use the advice given there to attempt to ameliorate it. However, really good reproductions, as can be found in some high-quality art books may not have half-toning, or have it so fine that it doesn't matter except at the most ridiculously high of resolutions. In these cases, scan it at at least 300dpi then adjust it in a graphics program as described for scanning from an original painting.

As always, Graphics labs such as en:WP:GL/IMPROVE, Commons:Graphics village pump and Commons:Graphic Lab can assist you if you find this difficult. Also, check the copyright status first. Bridgeman Art Library v. Corel Corp. and similar rulings in other countries mean that, in most cases, if the original is in public domain, a copy is as well. However, note that the United Kingdom has unusually strict copyright laws that may protect a heavily-restored image produced there. If in doubt, Commons:Licensing attempts to explain the full rules related to copyright, and Commons:Village pump may be able to help you if you are still uncertain.

Cropping[edit]

Try and leave a little whitespace around the image when you're scanning it in full. This makes sure you don't accidentally remove useful parts of the image or of its caption, or give the impression you have. Obviously, this may not be possible if the image goes right to the edge of the paper, but putting a piece of blank white paper behind it can help. (Don't worry about this when using black paper behind to prevent bleed-through.) Scan the image in multiple parts, if necessary—as mentioned in #General advice, support is available to stitch an image together from its parts.

When giving a detail from a larger image, try and trim it so that distracting details you do not intend to draw attention to are minimised in visual effect. For example:

This is a detail from a Punch cartoon—this Punch cartoon, in fact—that was being cropped for the English Wikipedia article on Gilbert and Sullivan. As such, The main image of Sullivan, and the tiny W. S. Gilbert were the important parts. Part of someone who is probably F. C. Burnand can be seen in the upper left-hand corner, but the crop avoids showing his face, so it doesn't attract too much attention. This detail is also from the lower-right corner of the original, so it's fairly sharply cropped on the right and bottom to avoid including (most of) the black line that frames the image as a whole, as having a thick black line on only two sides of an image would unbalance it. Serendipitously, the tiny bit of the black line that got left in on the lower edge and the bit of Burnand's moustache in the upper left completes the frame, creating a nice, even rectangle.

Caption[edit]

If a picture has a caption written in the same medium, it is better not to crop it, so that the information it may contain (original title, publisher, date, etc.) is immediately verifiable. Note that it is possible to produce a cropped version from the full scan with caption, while the reverse is not.

Always provide it with the captions, then upload any crops as a separate image

See also[edit]

- Help:Converting for advice on converting between document formats

- Help:Digitising texts and images for Wikisource

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Scanners use dpi (“Dots per inch”) to measure the resolution of the proposed scan. At 300 dpi, a 1 inch by 1 inch section (2.54 cm × 2.54 cm) of the original image becomes a 300 pixel by 300 pixel section of the scan.

- ↑ More on the topic: https://photo.stackexchange.com/a/69661/45210

External links[edit]

- Scantips

- Halftone scanning

- Scanning tips, tricks, tutorials and techniques - list of links

- SANE FAQ - SANE (Scanner Access Now Easy) - API for Linux scanner software such as XSANE